More

- Back to Lost Dog

- Read a deleted scene from Lost Dog

one

Swirling snow bit his cheeks, snapped at his blinking eyes. It was starting to stick to the ground. No good. Snow meant footprints, and cops got all over footprints. Just the other night, Jake watched a show where they busted some guy from his frigging sneaker. Nailed the sucker to the wall. The ground was mostly bark chips, which wouldn’t take a print for shit so long as he beat the snow. Just had to hurry.

The wind felt like a jagged blade at his back. Jake bent down and grasped the woman under her bony shoulders, pulled her toward the low concrete wall behind him. It was late, dark, colder than nobody’s business. Still, no telling who might show up outta nowhere at just the wrong moment. Some loon who wanted to play on the swings in the middle of the night, something like that. Had to get her out of sight. They’d find her anyway, but no reason to make it easy. If he was lucky, the snow might fall thick enough to help him out a little. Didn’t need much. Just time to get away and clean up. Maybe throw away his shoes. Then they could find her.

He dragged her through the gap in the wall, looking for the right spot. Plenty of options. Big concrete tubes the kids climbed on. A surge of wind rushed through the trees and kicked dead leaves and thickening snow along the ground. Teeter-totter creaked in the cold. He shuddered at the sound—pretty creepy for a playground, but maybe it was different by day. He stuffed the woman into one of the larger tubes, head first. Her shoes, black leather and heels, came off as he wrestled her legs into the narrow space. He tried to slip the shoes back onto her stiffening feet, but ended up tossing them into the tube beyond her head. They’d think it meant something if he took her shoes, but he didn’t want to chance being found with them. He stood up, caught his breath. Wiped his eyes.

A line of dark houses crowded the fence at the edge of the park, seemed to hunker down against the cold. No sign of life. Good. A single lamppost beyond the swings cast a silvery pall over the playground. He couldn’t make out much on the ground. No telling what kind of evidence he was leaving. The cops on TV could make a case out of anything. Broken twig could mean the chair. But there wasn’t a whole lot he could do about it, short of making himself scarce. He shuffled his feet back and forth to obscure his tracks, then brushed out the gouge in the bark chips left by the woman’s feet. He couldn’t tell if she’d bled much on the ground, though he knew her blood had gotten on his pants and coat. He’d be up half the night doing the wash.

He saw her purse at the foot of the slide. Grabbed it, dug through the contents. He found a wallet with a hefty wad of cash, a single key on a rabbit’s foot keychain. So much for good luck. He giggled, kept digging. Make-up,…cigarettes,…box of rubbers. He put it all into his pockets along with the stuff she’d thrown at him—a beer bottle and bits of junk she must’ve found on the ground as she scrambled around trying to get away. Evidence. He set the empty purse back near her tube. Make them think the whole thing was a robbery gone sour. He’d dump the wallet and anything else not worth keeping on the way home.

The wind died down, the thin snow now drifting softly out of the blackness above. He took a breath, let it out. Then he reached into his inside pocket, pulled out the gun. Empty now, it felt lighter. He wouldn’t have thought six measly bullets would make much difference, but they did. He tilted his head back and stared into the dark sky, stretched his arms over his head. Time to get going, but he couldn’t bring himself to move. She was safe now—he’d made sure of that. It was time to go, but the snow was falling and the air felt clean and crisp. And he wanted to look at her again. Touch her one more time.

He crept back through the gap in the wall, kneeled at the opening of her tube. It was dark, too dark to see more than a indistinct hump where she lay. He pulled off his gloves, reached out and felt her calf, her thigh, her skin. Still warm, barely. He stroked her legs and felt himself tremble in the darkness. What would they do with her? Would they understand what had happened? Why it had to happen? He felt his eyes water. Go home, Jake. But he couldn’t just yet. He wanted to lie down next to her for just a little while.

Except that would be really frigging stupid. He shook his head sharply and used the sleeve of his coat to smudge any fingerprints on her bare skin. He knew from TV that fingerprints didn’t last long on skin, but you couldn’t be too careful. He cast about and found a couple sheets of newspaper tossed up against the tube by the wind, carefully spread them over her. Couldn’t have said why. Not like she wouldn’t be found, anyway. Hell, he wanted her to be found. He stood, thrust his hands into his pockets. Turned away.

Long walk home. Way too late for a bus, but that would have been stupid anyway, him covered in blood. He kept to shadows, dodged headlights. Took the Steel Bridge across the river, dropped her wallet mid-span. Kept the cash. He didn’t think about her, concentrated instead on not being seen. He felt a little proud of himself, really, gliding like a ghost through the sleeping city. If anyone saw him, they’d wonder if he was even real. Heh.

It wasn’t till he was home, halfway through the laundry and feeling especially slick, that he realized he’d left his fucking gloves on the ground next to her dead body.

two

Not that he particularly cared for his sister’s incessant nagging, but if Peter McKrall had known he would find a dead woman in the park that morning, he’d have stayed home and listened to Abby bitch instead. The day started typically enough: Peter on the porch staring into the dreary morning sky, working out excuses. He’d overslept, and the sun was already up behind a colorless overcast. Snow crusted the grass and rhododendrons in the front yard, but the walk and street were too warm for the snow to stick. Peter expected this sort of thing back in Kain-tuck-ee, but since moving to Portland he’d never seen snow before New Years, and seldom afterward. Normally they kept the white stuff out in the sticks, where it belonged.

Rain. That’d be an excuse. He bent and stretched and thought about his niece Julie, asleep in the guest room. His sister and her husband David had come with Julie for Christmas and to check up on the house. Peter had been renting the place from them on the cheap since they moved to Seattle a couple years before, an arrangement originally intended to be temporary but which had grown permanent through the power of Peter’s inertia and the pleasure Abby took in having Peter in her debt.

He wondered how Julie had slept without Patch. Not well, probably. Shapeless, furless, one-eyed Patch, only one day younger than Julie herself. He’d bought Patch in the hospital gift shop when he came to see Abby the morning after Julie was born. The cashier, blue-haired and suspicious, had glared at him as he wandered the shop. All he’d wanted were some mints, but the cashier’s attention aroused his screw-you-bitch itch. Before he knew it, he had an insipid crystal figurine of an angel tucked inside his coat and Patch in his hand. “For my brand-new niece,” he said to the cashier, feeling the heat and satisfaction of his petty crime in his belly. He smiled and paid cash. “Altoids too, please.” The woman took his money, but he knew she’d be counting figurines the moment he left, despite the stuffed dog and brand-new niece. He left the angel on the sink in the men’s room, his pleasure in the theft already faded. But Patch he presented ceremoniously to Abby and child, as if he’d intended to give the gift all along. In those days, four years earlier, Patch had been fuzzy and tan with a brown spot around one button eye. Years of Julie’s affection had transformed the hound. She’d hugged and chewed him down to his woven skin, now grey and mottled from an endless succession of drool and wash-rinse-spin cycles.

The night before, when Patch turned up missing, Julie wept dime-sized tears, the Christmas presents she’d opened that morning unable to comfort her. Peter, Abby and David crawled under beds, peered behind plants, pawed through the trash. No Patch. Then Peter remembered he and Julie had pushed Patch on the swings during an afternoon jaunt to the park. No one recalled Patch coming home. By the time they realized what must have happened, night had fallen and a Columbia Gorge wind had kicked up out of the east, bitter cold and pushing snow. Too cold to be outside, and besides, while Irving Park held a certain daylight appeal, it wasn’t a place for after dark forays. Peter promised Julie he’d look for Patch when he went out for his morning run.

If he went out for his run. He was still working on excuses.

The front door opened behind him and Abby appeared, wrapped in her new Christmas robe, hair a brown-blond nest, one cheek blotchy with an impression of crinkled pillowcase.

“My God, it’s only seven,” Peter said. “I didn’t expect to see Her Majesty till noon.”

She stuck her tongue out at him. “I heard a noise in the living room. I wanted to make sure it wasn’t Julie sticking forks in electrical outlets.”

“That was me. About fifteen minutes ago.” He raised an eyebrow. “Your parental vigilance is an inspiration, Sis.”

“Don’t call me Sis,” she said, “or I’ll break your fucking arm.” She peered out at the leaden sky. “Aren’t you going to run?”

“What’s it to you?” A hint of defensiveness in his voice. But then he shrugged. “I suppose, sure, if nothing else comes up.”

“Lots of distractions this time of morning.”

“I was hoping for a monsoon, or maybe martial law. Killer asteroid. Something.”

Abby studied him. “Peter? How are you feeling?”

He felt himself flinch. “So you’re my doc now, too? Gonna check to make sure I’m taking my meds?”

“She’s got you on medication now?”

“Jesus, Abby. What do you think?”

“I don’t know what to think.”

“Can’t a guy just be a smart ass? Jesus!”

“Don’t be that way. I’m worried about you.”

He shrugged again, looked away. “Sorry.”

“It’s just a job. You’ll find another one.”

He shook his head. “It’s not that. Hell, I don’t even know if I want to find another one. I don’t know what I want to do. Maybe I want to go back to school. Or travel from small town to small town, solving local mysteries. Or go be a hermit in the mountains.”

“You’re already a hermit in this house. Peter, there’s no rush. Take your time. Listen, I talked to Dave, and we’re okay with letting you skip the rent for a couple of months.”

Peter’s cheeks grew warm. “Thanks. Hopefully not for too long.” He hated to have to ask for help from his sister.

“There’s one condition,” she continued. “You’ve got to stop the drinking binges—”

The heat in his cheeks suddenly surged down into his chest. “That was one time, Abby!” he snapped. “I just lost my fucking job. I think I’m entitled—”

She reached up and put a finger to his lips. “You’re the one with no job and a two-day hangover for Christmas—not me. If you’re going to throw your money away in seedy little bars, you can’t expect Dave and me to subsidize the rent. You need to take care of yourself.”

He pulled his head back, scowling. Even worse than accepting help from Abby was admitting when she was right. He could hardly afford to make a habit of bar-hopping, seedy or otherwise, especially if he spent the way he had the other night. Certainly his wallet had been lighter than expected when he checked it the next morning—probably over generous tipping the bartender and cab driver. Not that he could remember. “We can fight this out later,” he muttered.

Abby lowered her hand. “I’ll win. I always win. Break your arm if I have to.”

He didn’t react, just stared out at the sky, knowing she was right. Some things never changed. If he had the balls God gave a gopher, he’d tell her to fuck off. Move out, let her deal with the hassle of finding a real tenant. She’d beat the living shit out of me, he thought, and chuckled.

Abby tilted her head and narrowed her eyes. “What’s so funny?”

“Just easily amused.” He clapped his hands. “Okay, time to run. Doc says exercise, by God I’m gonna exercise.”

She rolled her eyes and started back inside, then stopped. “What about Patch?”

“Don’t worry. I’ll look for him while I’m out.”

“Her. Patch is a Her.”

“Right. Her. She’s always been a boy to me.”

Abby smiled and pulled her robe tight. “Run hard. Don’t fret. Find Patch.” She patted him on the cheek, then slipped inside and closed the door.

Blizzard. That’d be an excuse. It was Sunday. If he looked first and found Patch, he could put him—her, it, whatever—inside before Julie woke up, and still have time to run before the traffic started. Not like he ever ran very far. Besides, he wouldn’t feel like searching after his run. He’d feel like drinking coffee and staring into space and begging his sister to rub his feet. Not that she would. She’d stop charging rent, but she wouldn’t rub his fucking feet.

Patch then. His breath billowed white behind him as he trotted down the steps and headed up the street. As he passed the tidy little houses to either side, he imagined they stared at him with dark windows. Peter had lived on this street for two and a half years, but he still didn’t know most of his neighbors. Portland Mole People, he called them, huddled inside their Portland bungalows, wrapped in Portland earth-tone clothes, with their groomed yards and flower beds filled with purple and green kale. He seldom saw them, though when he did most were friendly enough in a distant, I’ll-say-Hi-but-won’t-tell-you-my-name sort of way. This distinction served to remind him he didn’t live in Lexington anymore, where a careless hello bought you a cup of instant coffee and insight into a stranger’s family history going back four generations.

Half a block up from his house, Peter came to a break in the kale-clad yards, a little shrub and posy-lined path called the Klickitat Trace which formed the east entrance to Irving Park. The asphalt path ran west through the park between two soccer fields, then turned south and rose among tall cedars, firs, maples and elms. At the end of the path, where Ninth abutted the south edge of the park, huddled the bark-chip floored playground.

The park was empty. A breeze kicked up at his back, remnants of the east wind. He’d dressed for running—sweats, gloves, earmuffs. He rubbed his arms and hoped he’d find Patch quickly. Juniper bushes sheathed in glassy ice lined the path near the playground.

The trees had broken up the snowfall so that only a light dusting covered the ground. Numerous lumps that might be a stuffed animal hid under the snow. Peter thought back to what he and Julie had done the day before. Mostly they’d stuck to the play structure, which served alternately as sailboat or castle, or to the swings—a tremulous endeavor as Peter suffered the final dregs of his extended hangover. Under the play structure, he found an empty forty-ouncer and a sheaf of rolling papers he hadn’t noticed the day before. A pack of matches with the heads all burnt. A condom wrapper. But no Patch. The swings looked no more promising. Peter kicked through the bark chips as the wind blew glittering spirals of snow off the trees above. It might have been pretty if he hadn’t felt so damned cold.

At the edge of the playground, over a fence that separated the park from someone’s backyard, Peter saw a big yellow mutt staring at him. Bored with his search, Peter stared back. “Have you seen Patch?” he said. “She’s a dog too.” The mutt stared, motionless. “Hello-o-o-o, pooch. Bark-bark?”

“Hey, bud! You harassing my dog?” Peter jumped as an old man appeared on the back porch of the house. He fixed Peter with a scowl, his forehead wrinkled, white caterpillar eyebrows bunched beneath a bald, liver-spotted pate. He wore in a bulky parka and rubber hip waders. The dog didn’t move.

“I was just—” Peter lost his words beneath the weight of the old man’s glower.

But then the old man grinned. “Had ya there!” he said and laughed. He whistled. “Come on, Bo! Going fishing!” The dog released a clipped bark, then bounded onto the porch. The old man tussled its head and neck. “Hope you find Paunch, bud!” Without another word, man and dog disappeared into the house.

Peter stood staring at the empty porch for a moment. Crazy old man. That might be an excuse. He turned his attention back to the playground. Time to find that damn Patch before he froze his ass off.

They’d skipped the slide. Julie didn’t like the height, and besides, it smelled like someone had pissed in the landing zone. The teeter-totters were hopeless. Julie wanted to ride, but Peter’s hundred-and-eighty pounds threatened to launch her thirty-five into orbit. Still, Julie had wandered over that way once, so Peter nosed around them for a moment or two. Cigarette butts. But no Patch. He himself had vetoed the merry-go-round. “You wouldn’t want Uncle Pete to toss your mommy’s Christmas cookies, would you?” No, Unker Pete. With diminishing hope, Peter looked under the play structure again. He found old Popsicle sticks and the end of a half-eaten candy cane. Still no Patch.

He considered returning later with Julie, putting her Patch-radar to work. Then he recalled that as their time had crept to an end the day before, Julie had drifted toward the far end of the playground to a big jumble of concrete cylinders, sections of sewer pipe painted in playful colors. Some stood on end, some lay on their sides, all different lengths and diameters, all big enough for a four-year-old to crawl through. A low wall encircled them with an opening that faced the playground. Peter had been tired—no way could he keep up with the hummingbird energy of a pre-schooler—but he’d let Julie explore for a few minutes before he coaxed her back to the house.

Frostbite. Not nuclear winter, but Abby could hardly argue. Some pipes were three or four feet around and as much as ten feet long. The wall had captured no end of dead leaves and old newspapers tossed by the Gorge wind. An extra thick layer of blown snow had collected as well. He found a brown leather purse, nothing inside, and a pair of mucked-up gloves. He kicked up a doll head and a mud-caked pink bandana. No Patch. The pipes cut the wind, and the exertion of clambering among them warmed him up a little. At the end of one long tube, his foot slid on ice. Then the ice cracked and his foot sank into a puddle. Thick, dark fluid welled up and soaked the snow black. He lifted his shoe. The fluid left a dark purple stain on the dingy white leather.

“Damn it,” he grumbled. He was wondering if Patch was worth all this. A couple of sheets of newspaper covered a heap of trash or something inside the tube. He made out ads for car dealerships and home furnishings. After-Christmas sales. Bargains bargains bargains. Sticking out from under the newspaper at the end of the pipe he saw a round protrusion of greyish brown cloth.

“Finally,” he muttered, grabbing the cloth. He abruptly let go. It wasn’t Patch. It was firm and cold and it resisted his tug. He gazed at the newspaper. He knew transients often slept in the park. The pipe might offer shelter from the nasty east wind, but maybe not enough on a really cold night. A bubbling, watery feeling filled his gut. He looked around helplessly, but no one was there. Not even the crazy old man and his dog.

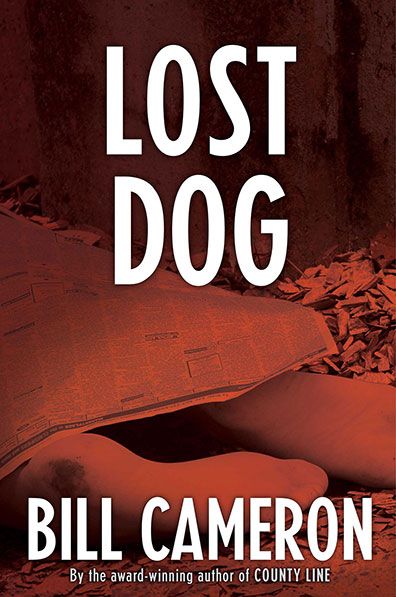

“This is such bullshit,” he said. He lifted the newspaper anyway. Morbid curiosity pushed him that far. One nylon-clad foot was tucked under the other, both shoeless. Another sheet of newspaper covered the upper half of the body, but he saw a red skirt hiked up to a contorted waist, pale underwear ripped at the seams. Two pallid blotchy hands, their painted fingernails split, protruded from under the paper and seemed to grope toward the knees. Nylons down around the ankles, legs blue-white and twisted. A red-black hole below the hip. Dark blood had drained from the hole, down out of the lip of the pipe and frozen. He’d stepped in it. From the size of the flow, Peter felt certain there were more holes in the woman. Lots of them, maybe. Jesus. The watery feeling dropped through his bowels into his legs, and he tried to stand. Gravity resisted his effort. Vaguely, he decided to leave the other piece of newspaper in place. Morbid curiosity was one thing. Gazing at a pale, dead face was something else altogether.

But, hey, dead body. That was an excuse.