When a grave at the Pioneer Cemetery is robbed, Melisende Dulac sets out to track down the perpetrator and, in the process, solve a century-old mystery.

Where To?

A rumination on humanity's long-term prospectsCertain futurists have long discussed the idea that in order for “our species to survive,” we must become first interplanetary and then interstellar. Though I agree, I admit to the possibility we might survive on Earth for a long time1The average mammalian species exists for one-to-two million years, so when I say a “long time,” I’m thinking at least that, if not longer. A really long time time pushes up against changes in the sun’s behavior that would make survival on Earth impossible, even if we don’t kill ourselves or poison our world first. if we can just get our heads out of our asses.

The off-planet idea is also a long shot, because most of us are stupid and aggressive and cruel and selfish. So, . . . maybe. Probably not, but maybe.

But if we do get off-planet and establish a viable existence elsewhere, what will it look like? Our fiction takes faster-than-light for granted, whether it’s warp drives, hyperspace, or wormholes, but physics says otherwise. Barring an impossible-to-predict theoretical breakthrough, we’ll reach the stars only via a long, slow slog.

The first interstellar travelers will most likely be robots. How “smart” they’ll be is hard to say,2Advances in artificial intelligence might make them very smart, though I’ll take no bets on whether that intelligence can or will ever achieve self-awareness. There’s also the possibility of human/machine synthesis that could make interstellar travel more accessible. But that requires more hard to predict breakthroughs, and also encourages weird Singularity fanbois to brigade your social media to endlessly bloviate. No one needs that. (No comment on my own bloviating here.)

but they won’t be big and they won’t be fast. Consider how much energy is required to accelerate even a small probe to speeds necessary to reach the outer planets of our own solar system. Such “local” trips still take several years. The Voyager probes needed nearly five decades to reach interstellar space, and not all scientists even agree they have. The nearest star is vastly farther.

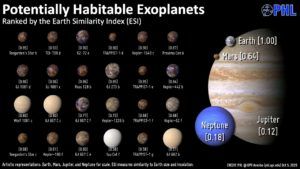

An intentionally designed interstellar probe almost certainly will be faster, and sure, we’ll keep working on new technology—as long as our resources (human and material) last.3In fact, it’s likely later generations of probes may pass earlier generations en route to their destinations. If all goes well, we might reach a point where we can accelerate modest probes to meaningful fractions of the speed of light, and aim them at stars that look promising based on data from the next generation of space telescopes like Webb and beyond. But it will still take multiple human lifetimes to cross interstellar distances. Human beings aren’t making that trip any time soon.

Meanwhile, back home, most of us are still fucking things up. Cloned Donald Trump XVII will be threatening genocide via urine flood if the Futrolibs don’t line up to fellate him. But maybe we’ve got space stations,4Though if they’re created by Elon Musk, they’ll either randomly burst into flames or you’ll get stuck with an expensive software update should you want oxygen in your atmosphere mix. and planetary colonies5Colony, given its horrific history, is a word I use here with some caution. It’s not one I’d use at all if we were invading somewhere with indigenous life. by then. If we’re lucky, they’ll be insulated enough that when the Earthbound die off, off-planet folks will survive.

The rest of the solar system is beautiful and full of cool stuff, but none of it is prime real estate for human habitation. Still, we might be able to Expanse it. And maybe we learn how to turn an asteroid space station into an interstellar vessel. By then, a trickle of data from those slowpoke probes might even be radioing back, letting us know the most promising destinations.6Of course, if those probes are self-aware, and they remember us well-enough, they might feed us bad information. Who could blame them?

Maybe we head off in multiple directions. And maybe a few of those vessels find a place to call home. Maybe a few of those new human settlements survive, and thrive, and send out their own vessels. Maybe we really do become an interstellar “species.”

Which brings me to those scare quotes. If physics tells us we’re unlikely to ever wormhole to Tau Ceti, biology tells us evolution doesn’t stop. The passing decades, centuries, millennia necessary to get “us” from here to there, wherever there is, will also contribute to “us” becoming less us and more them. Mutation and the environmental pressures of living in asteroidal cans or on weird new worlds might punctuate the changes. Should the descendants of the Teegarden’s Star vessel some millennium meet up with the descendants of the Trappist vessel, will they recognize each other as cousins? If that millennium isn’t too far off, sure, probably, though the differences might be shocking. But will the two groups still be the same species?

Maybe the galaxy goes Star Trek, with differences such that we can no longer interbreed7Though Spock is allowed. Spock is always allowed., but can still share wardrobes. But maybe directed evolution and genetic engineering forces separate populations down wildly divergent paths, such that a DNA sequence might show our shared heritage, but to look at each other we might be chordates contemplating cephalopods. What are we then? Are we all humanity? Did our species survive in the interstellar vastness?

And if us, today, used a time machine to see how things turned out, would we say, “Yes, we made it,” or, “Holy shit, what have we become?”

- 1The average mammalian species exists for one-to-two million years, so when I say a “long time,” I’m thinking at least that, if not longer. A really long time time pushes up against changes in the sun’s behavior that would make survival on Earth impossible, even if we don’t kill ourselves or poison our world first.

- 2Advances in artificial intelligence might make them very smart, though I’ll take no bets on whether that intelligence can or will ever achieve self-awareness. There’s also the possibility of human/machine synthesis that could make interstellar travel more accessible. But that requires more hard to predict breakthroughs, and also encourages weird Singularity fanbois to brigade your social media to endlessly bloviate. No one needs that. (No comment on my own bloviating here.)

- 3In fact, it’s likely later generations of probes may pass earlier generations en route to their destinations.

- 4Though if they’re created by Elon Musk, they’ll either randomly burst into flames or you’ll get stuck with an expensive software update should you want oxygen in your atmosphere mix.

- 5Colony, given its horrific history, is a word I use here with some caution. It’s not one I’d use at all if we were invading somewhere with indigenous life.

- 6Of course, if those probes are self-aware, and they remember us well-enough, they might feed us bad information. Who could blame them?

- 7Though Spock is allowed. Spock is always allowed.

When not tending his chickens, BCMystery shapes unruly words into captivating people caught in harrowing situations. As Bill Cameron, his work includes the critically-acclaimed Skin Kadash mysteries and, as W.H. Cameron, the high desert mystery Crossroad. He’s presently at work on a historical mystery set on the Oregon coast.

When not tending his chickens, BCMystery shapes unruly words into captivating people caught in harrowing situations. As Bill Cameron, his work includes the critically-acclaimed Skin Kadash mysteries and, as W.H. Cameron, the high desert mystery Crossroad. He’s presently at work on a historical mystery set on the Oregon coast.